“It’s natural. Black people suffer externally in this country. Jewish people suffer internally. The suffering’s the mutual fulcrum for the blues”.

Michael Bloomfield

You have to set the scene. The early 1960’s on Chicago’s South Side. A packed house in a local blues joint. The crowd is dropping a few drinks, cigarettes smoldering in ashtrays, clouds of blue gray smoke drift lazily towards the ceiling. It’s late in the evening and the patrons are swaying and singing along to Muddy Waters who sits on a stool on a make shift stage, his guitar making electric Delta magic. The big man is bellowing and hollering the blues, working the crowd into a hypnotic haze, disconnecting them all from the current scene.

A master bluesman and his crew transporting the crowd down the blues highway.

A young, thickset, pimply-faced white kid enters the club carrying a guitar case. He works his way through the crowd. Most don’t notice him at first and the ones that do see him coming dismiss him as just some kid who is somewhere he shouldn’t be. The kid climbs the few rickety steps onto the bandstand and says ‘Hi, do you mind if I sit in?” as he is plugging his guitar into an amp. Muddy stares at the kid and before he can kick him off the stage, the kid launches into a blistering solo perfect tuned to Muddy’s melody line. A slow smile creeps across the Big Man’s face and the band continues on into the night with their new addition keeping up with the veterans easily.

This scene would continue to occur several more times at various clubs through out the city. The same kid would hop up on stage and push his way into impromptu jams with some of the biggest names in Chicago blues like Otis Rush, Magic Sam, the three Kings (B.B., Freddie and Albert), Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry and others.

That kid was Michael Bloomfield.

Not long after he became one of the very first of the blues-rocks Gods.

Bloomfield was born to a well-to-do Jewish family on Chicago’s North Side on July 28th, 1943. His first exposure to the music that would later become his most enduring passion was through the radio where he would pick up southern stations filling the night air with R&B, blues and rockabilly. He received his first guitar for his Bar Mitzvah and took to it immediately. With the help of his families’ domestic help, Bloomfield often snuck into local clubs to hear his radio idols live. When it became apparent to his parents that Michael’s formal education was being put aside for his self-made musical schooling, he was sent to the East Coast to a boarding school for a time. Eventually he graduated from a school for ‘troubled’ youths in Chicago. Eschewing the family business as a future career (his family made their money in restaurant catering equipment), Bloomfield threw himself into his musical career. It didn’t take long for him to become one of the most sought after session men in Chicago as well as a ‘sit in’ guitarist for countless local area blues bands.

While still a young man, Bloomfield began to manage the coffee shop and club, The Fickle Pickle, where he would feature some of the same legends he ‘joined’ on stage as a youngster. While he was working at the Pickle, Bloomfield also worked at his grandfathers’ pawnshop and at the Jazz Record Mart. As he continued to make forays into the blues, he began to turn his attention to the acoustic blues of the Delta. To his surprise, a number of the same blues players that he was discovering were alive and well and had relocated to Chicago. The ‘Pickle’ became one of the premiere showcases and launch pad for the revival of several of these legends including Big Joe Williams and Sunnyland Slim.

Famed Columbia Records producer John Hammond Sr. had heard about the young blues guitar slinger and signed him to a contract in 1964. This was a rarity at the time as Columbia was a label that had stayed away from the blues. Despite the fact that Bloomfield’s work was top notch, his initial sessions failed to result in a produced album (the sessions were released later after his death). All the while, Bloomfield was a regular at The Blue Flame, a notorious South Side blues bar.

After he walked away from Columbia, Bloomfield signed with Elektra Records. Producer Paul Rothchild approached Bloomfield and asked him to join fellow Elektra Records artist, harmonica player Paul Butterfields group. In an interview Bloomfield said, “I didn’t like him, and he didn’t like me (speaking of Butterfield). It was the record companies choice – Rothchild wanted me”. The band, which included guitarist Elvin Bishop and drummer Sam Lay, were lauded by both blues and rock fans alike for their faithful renditions of blues standards. But these blues standards had the additional kick of Bloomfield’s guitar work.

The initial sessions were scrapped when Rothchild convinced the label that the band could do ‘better’. Through some phone calls, Rothchild managed to get the band on the marquee for the Newport Folk Festival. Rothchild also knew that this band was beyond his capacity to manage and essentially gave them over to famed, and some times nefarious, manager Albert Grossman.

Prior to Newport Bloomfield finagled a chance to meet with Bob Dylan. Dylan was playing in club in Chicago when he and Bloomfield met. Dylan explained in ‘Michael Bloomfield: If You Love These Blues”, He (Bloomfield) came down and said that he played guitar. He had his guitar with him and I said “Well what can you play? “And he played all kinds of things – Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Boy Williamson, that type of thing. He just played circles around anything I could play, and I always remembered that.’

From that meeting, Dylan invited him to play lead on his album ‘Highway 61 Revisited’. When Dylan played Newport Folk Festival, he needed a back-up band and he immediately hired The Butterfield Blues Band. Bloomfield and crew were on stage when Dylan ‘plugged in’ for ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ much to the chagrin of pure folk fans everywhere. To rock and rollers, it was a seminal moment in music history.

Post Newport, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band released their first album to high praise from the critics. However fans were having a hard time cozying up to the release. Things changed quickly with the 1966 release ‘East/West’ (which is considered by many to be one of the finest examples of blues rock ever put to vinyl).

Bloomfield left The Butterfield Blues Band in 1967 and formed up Electric Flag with Nick Gravenites, Mark Naftalin, Buddy Miles (later with Hendrix) and Ira Karmin. Despite the accumulation of talent, the Flag was short-lived, recording one album, ‘Long Time Coming’ in 1968, before disbanding. Bloomfield actually left the band shortly before the release of the disc. According to various accounts, the break up was a result of personality clashes in the band and rampant drug use.

Almost immediately Bloomfield returned to the studio, recording one side of Al Kooper’s ‘Super Session’ album in 1968. His recurring insomnia and his own drug problems forced him to return to his San Francisco home before being able to complete the project. Kooper brought in the recently available Stephen Stills to record side two. According to Neil McGarity, “… Bloomfield’s astonishing display of technique and his cool, self assured delivery” made him a bona fide guitar God and something that he spent the rest of his life trying to shake off. ‘Super Sessions’ became the biggest selling and most popular album associated with Bloomfield.

The pair, Kooper and Bloomfield, recorded ‘Live Adventures Of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper’ in 1969 but again the insomnia and drug use forced Mike out before completing the project. Replacement guitarists Carlos Santana and Elvin Bishop subbed for Bloomfield on the final few nights.

Bloomfield dropped out of music for the next few years opting instead to record soundtracks for a host of documentaries and art films (Steelyard Blues, Medium Cool and Andy Warhol’s Bad) and even recorded soundtracks for several porno movies.

In 1973, Bloomfield hooked up with John Hammond Jr. and Dr. John to record the album ‘Triumvirate’. The project was so poorly received, the group disbanded. In 1975 he tried again with the group ‘KGB’ which featured Carmine Apice (Vanilla Fudge) and Rich Grech (Traffic, Blind Faith and the Gram Parsons Band). Again, the band failed to gel and quickly disbanded.

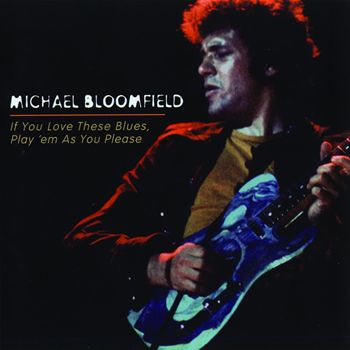

Bloomfield continued to record solo projects off and on for the remainder of his life, none of them capturing the searing abilities of his pre-heroin youth. In 1976, in association with Guitar Player magazine, Bloomfield released ‘If You Love These Blues, Play ‘Em As You Please’. It was an instructional disc showcasing a variety of blues and the necessary techniques. It was nominated for a Grammy.

On November 15th, 1980, Bloomfield joined Dylan on stage at the Warfield Theatre in San Francisco and tore up a version of ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, a song that they had recorded 15 years prior. The stage was set for a possible comeback for Bloomfield.

But it was not to be. Michael Bloomfield was found dead in his car of a drug overdose in San Francisco on February 15th, 1981. Even in death, Bloomfield is a somewhat murky figure and difficult to pin down. There are stories that he had actually died at a party in San Francisco and two unidentified men who were at the party drove his body to the place where it was later discovered.

In a 1979 interview with Blues Guitar Magazine, Bloomfield seemed to sum up his entire attitude towards his chosen profession. “I didn’t relate to being a rock star at all. I read a lot of stuff about all that, but it wasn’t real for me. I was never into it.” Whether he was into or not, whether it was accidental or on purpose, Michael Bloomfield was a rock star; a star that imploded far too soon.